Proclamation of Philippine Independence

September 30, 2020

During the Spanish-American War, Filipino rebels led by Emilio Aguinaldo proclaim the independence of the Philippines after 300 years of Spanish rule. By mid-August, Filipino rebels and U.S. troops had ousted the Spanish, but Aguinaldo’s hopes for independence were dashed when the United States formally annexed the Philippines as part of its peace treaty with Spain.

The Philippines, a large island archipelago situated off Southeast Asia, was colonized by the Spanish in the latter part of the 16th century. Opposition to Spanish rule began among Filipino priests, who resented Spanish domination of the Roman Catholic churches in the islands. In the late 19th century, Filipino intellectuals and the middle class began calling for independence. In 1892, the Katipunan, a secret revolutionary society, was formed in Manila, the Philippine capital on the island of Luzon. Membership grew dramatically, and in August 1896 the Spanish uncovered the Katipunan’s plans for rebellion, forcing premature action from the rebels. Revolts broke out across Luzon, and in March 1897, 28-year-old Emilio Aguinaldo became leader of the rebellion.

By late 1897, the revolutionaries had been driven into the hills southeast of Manila, and Aguinaldo negotiated an agreement with the Spanish. In exchange for financial compensation and a promise of reform in the Philippines, Aguinaldo and his generals would accept exile in Hong Kong. The rebel leaders departed, and the Philippine Revolution temporarily was at an end.

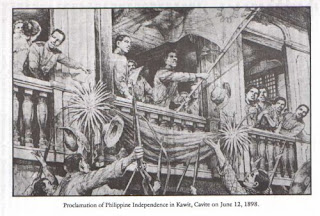

In April 1898, the Spanish-American War broke out over Spain’s brutal suppression of a rebellion in Cuba. The first in a series of decisive U.S. victories occurred on May 1, 1898, when the U.S. Asiatic Squadron under Commodore George Dewey annihilated the Spanish Pacific fleet at the Battle of Manila Bay in the Philippines. From his exile, Aguinaldo made arrangements with U.S. authorities to return to the Philippines and assist the United States in the war against Spain. He landed on May 19, rallied his revolutionaries, and began liberating towns south of Manila. On June 12, he proclaimed Philippine independence and established a provincial government, of which he subsequently became head.

His rebels, meanwhile, had encircled the Spanish in Manila and, with the support of Dewey’s squadron in Manila Bay, would surely have conquered the Spanish. Dewey, however, was waiting for U.S. ground troops, which began landing in July and took over the Filipino positions surrounding Manila. On August 8, the Spanish commander informed the United States that he would surrender the city under two conditions: The United States was to make the advance into the capital look like a battle, and under no conditions were the Filipino rebels to be allowed into the city. On August 13, the mock Battle of Manila was staged, and the Americans kept their promise to keep the Filipinos out after the city passed into their hands.

While the Americans occupied Manila and planned peace negotiations with Spain, Aguinaldo convened a revolutionary assembly, the Malolos, in September. They drew up a democratic constitution, the first ever in Asia, and a government was formed with Aguinaldo as president in January 1899. On February 4, what became known as the Philippine Insurrection began when Filipino rebels and U.S. troops skirmished inside American lines in Manila. Two days later, the U.S. Senate voted by one vote to ratify the Treaty of Paris with Spain. The Philippines were now a U.S. territory, acquired in exchange for $20 million in compensation to the Spanish.

In response, Aguinaldo formally launched a new revolt–this time against the United States. The rebels, consistently defeated in the open field, turned to guerrilla warfare, and the U.S. Congress authorized the deployment of 60,000 troops to subdue them. By the end of 1899, there were 65,000 U.S. troops in the Philippines, but the war dragged on. Many anti-imperialists in the United States, such as Democratic presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan, opposed U.S. annexation of the Philippines, but in November 1900 Republican incumbent William McKinley was reelected, and the war continued.

On March 23, 1901, in a daring operation, U.S. General Frederick Funston and a group of officers, pretending to be prisoners, surprised Aguinaldo in his stronghold in the Luzon village of Palanan and captured the rebel leader. Aguinaldo took an oath of allegiance to the United States and called for an end to the rebellion, but many of his followers fought on. During the next year, U.S. forces gradually pacified the Philippines. In an infamous episode, U.S. forces on the island of Samar retaliated against the massacre of a U.S. garrison by killing all men on the island above the age of 10. Many women and young children were also butchered. General Jacob Smith, who directed the atrocities, was court-martialed and forced to retire for turning Samar, in his words, into a “howling wilderness.”

In 1902, an American civil government took over administration of the Philippines, and the three-year Philippine insurrection was declared to be at an end. Scattered resistance, however, persisted for several years.

More than 4,000 Americans perished suppressing the Philippines–more than 10 times the number killed in the Spanish-American War. More than 20,000 Filipino insurgents were killed, and an unknown number of civilians perished.

In 1935, the Commonwealth of the Philippines was established with U.S. approval, and Manuel Quezon was elected the country’s first president. On July 4, 1946, full independence was granted to the Republic of the Philippines by the United States.

HISTORICAL FACTS

FILIPINOS celebrate Independence Day every 12th of June, but did you know that it was on July 4, 1946 that we originally obtained our freedom?

- President Diosdado Macapagal signed an executive order on May 17, 1962 that “moved” the Philippines’s Independence Day from July 4, 1946 to June 12, 1898. This was on the basis of the Declaration of Independence by General Emilio Aguinaldo in Kawit, Cavite—“to correct history and better the national aspirations of the Filipino people.”

- The struggle for independence started on April 27, 1521, when the Spanish explorer, Ferdinand Magellan, was killed in Mactan, Cebu, in the hands of native freedom fighters led by Lapu-Lapu.

- The Philippine archipelago was not yet a nation then, but composed of small warring tribes. It was only after more than 300 years of Spanish colonization and 50 years of American occupation that the archipelago was united into a semblance of a nation.

- The war for national independence began on July 7, 1892 when the Katipunan was founded by Andres Bonifacio. In 1894, Bonifacio himself inducted Emilio Aguinaldo into the Katipunan. But even as a member of Katipunan, on January 1, 1895, Emilio Aguinaldo was appointed as Cavite’s capitan municipal. He was the seventh of eight children born to a wealthy Chinese mestizo family in Cavite on March 22, 1869. His father, Carlos Aguinaldo y Jamir, was the town mayor or gobernadorcillo of Old Cavite.

- The first shot was fired during The Cry of Balintawak on August 26, 1896. The first encounter was in sitio of Pasong Tamo, Bulacan, where the Katipunan suffered more than 3,000 casualties. The 1896 revolt spread to the other provinces. Jose P. Rizal was executed in Bagong Bayan (Luneta) on Dec. 30, 1896, with charges of being the instigator of the revolution.

- In March of 1897, the two Katipunan factions of Bonifacio and Aquinaldo met in Tejeros for an election. The assembly elected Aguinaldo as president, in a possibly fraudulent poll that aggravated Bonifacio. He refused to recognize Aguinaldo’s government. Two months later, in response, Aguinaldo had him arrested.

- Bonifacio and his younger brother were charged with sedition and treason, and were executed on May 10, 1897. Aguinaldo also ordered the assassination of Gen. Antonio Luna in Cabanatuan, Nueva Ecija. These were among the reasons why he had only limited support, even in his native province of Cavite and in some neighboring areas.

- In June of 1897, Spanish troops defeated Aguinaldo’s forces and retook Cavite. The rebel government regrouped in Biak na Bato, a mountain town in Bulacan. Aguinaldo and his rebels came under intense pressure from the Spanish, and had to negotiate surrender later that same year.

- In mid-December, 1897, Aguinaldo and his government ministers agreed to dissolve the rebel government and go into exile in Hong Kong. In return, they received legal amnesty and an indemnity of 800,000 Mexican dollars. An additional $900,000 was given to the revolutionaries who stayed in the Philippines. On December 23, Emilio Aguinaldo and other rebel officials arrived in British Hong Kong. Despite the amnesty agreement, the Spanish authorities began to arrest true and suspected Katipunan supporters in the Philippines, prompting a renewal of rebel activity.

- In 1898, the United States naval vessel USS Maine exploded and sank in Havana Harbor, Cuba. This instigated the Spanish-American War on April 25, 1898. Spaniards still controlled the cities of Cebu, Iloilo, Bacolod, Legazpi, Zamboanga, Vigan and their adjacent towns.

- Aguinaldo sailed back to Manila with the US Asian Squadron, which defeated the Spanish Pacific Squadron in the May 1 Battle of Manila Bay. By May 19, 1898, Aguinaldo was back on home soil.

- On the 12th of June, 1898, the revolutionary leader declared the Philippines independent, with himself as the unelected President. Emilio Aguinaldo was officially inaugurated as the first president and dictator of the Philippine Republic in January of 1899. Prime Minister Apolinario Mabini headed the new cabinet.

- However, the United States did not recognize this new independent Filipino government, or any single foreign government. The Filipino people did not ratify the 1899 Malolos Constitution, which gave “retroactively” Aguinaldo his “emergency” powers to declare a dictatorial government in 1898.

- Meanwhile, close to 11,000 American troops cleared Manila and other Spanish bases of colonial troops and officers. On December 10, Spain surrendered its remaining colonial possessions (including the Philippines) to the US in the Treaty of Paris. Spain had handed over direct control of the Philippines to the United States in return for $20 million, as agreed in the Treaty of Paris.

- In February of 1899, the first Philippines Commission from the US arrived in Manila to find 15,000 American troops holding the city. By November, Aguinaldo was once again running for the mountains, with his troops in disarray. However, the Filipinos fought on against this new imperial power, turning to guerrilla warfare when conventional fighting failed them. On April 1, 1901, Aguinaldo formally surrendered, swearing allegiance to the United States of America. He then retired to his family farm in Cavite.

- In 1935, the Philippine Commonwealth held its first elections after decades of American rule. Then aged 66, Aguinaldo ran for president, but was soundly defeated by Manuel Quezon.

- When Japan invaded and seized the Philippines during World War II, Aguinaldo cooperated with the occupation forces. He joined the Japanese-sponsored Council of State, and made speeches urging an end to Filipino and American opposition to the Japanese occupiers. After the US recaptured the Philippines in 1945, the septuagenarian Aguinaldo was arrested and imprisoned as a collaborator. However, he was quickly pardoned and released, and his reputation was not too severely tarnished by this war-time indiscretion.

- Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt could have sided with the American Navy top brass in October 1944 and avoided American casualties in the Philippines. The admirals wanted to bypass the Philippines, drive the Japanese from Formosa (now Taiwan) and attack mainland Japan from there. Gen. Douglas MacArthur appealed to President Roosevelt. The general said: “To bypass the Philippines would admit the truth that we had abandoned the Filipinos and would not shed American blood to redeem them.” President Roosevelt agreed with General MacArthur and authorized the October 20, 1944, landing at Leyte. United States lost more than 20,000 American lives in recapturing the Philippines from the Japanese invaders in 1944-1945.

- Elections were held in April 1946, with Manuel Roxas becoming the first president of the independent Republic of the Philippines. The United States ceded its sovereignty over the Philippines on July 4, 1946, as scheduled. However, the Philippine economy remained highly dependent on United States markets—the Philippine Trade Act, passed as a precondition for receiving war rehabilitation grants from the United States, exacerbated the dependency with provisions further tying the economies of the two countries. A military assistance pact was signed in 1947 granting the United States a 99-year lease on designated military bases in the country.

- In 1962, President Diosdado Macapagal asserted pride in Philippine independence from the United States in a highly symbolic gesture; he moved the celebration of Independence Day from July 4 to June 12, the date of Aguinaldo’s declaration of the First Philippine Republic. Aguinaldo himself joined in the festivities, although he was 92 years old and rather frail. On February 6, 1964, the 94-year-old first president of the Philippines passed away due to a coronary thrombosis. He left behind a complicated legacy.

Comments

Post a Comment